The following essay was originally published on Medium.com on April 28, 2021

I. Thrashing

Kids screaming. News alerts flashing. Zoom call pending. Will you work out today? Maybe. Will you cook today? You’ll try. Will you read a book? Okay, enough.

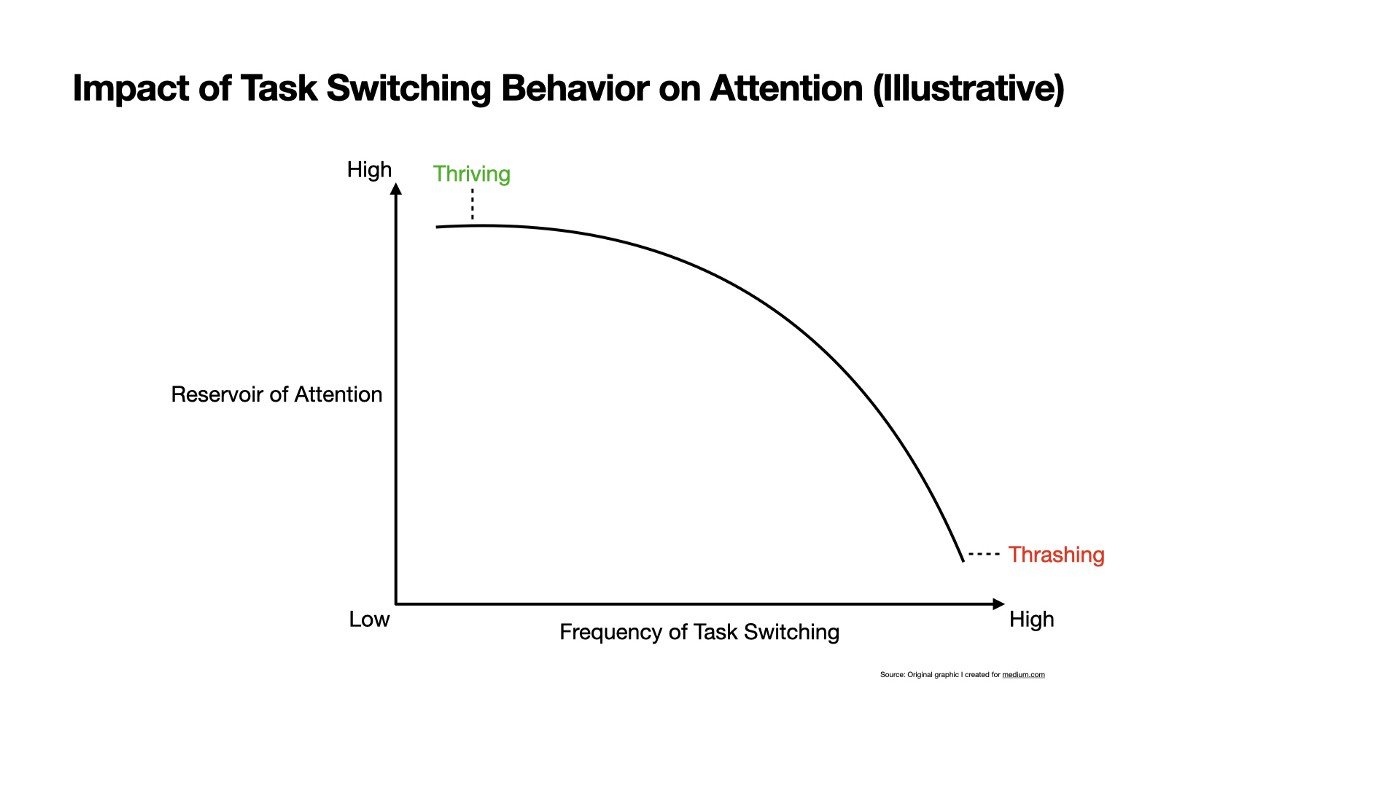

You have 100 things to do today and 18 waking hours to do them, give or take. You could divide your time into equal parts and assign every task the same amount of time. In that case, everything you want to do would get 10.8 minutes of your time. That isn’t much. And then, of course, there’s the time you need to budget to change locations, or outfits, for example, in between tasks. These are concrete examples, but the most important cost of getting things done is also the least thought of: the attention cost of task switching.

Psychologists have a term for this effect: It’s called a switch cost. Every time you switch from task A to task B, your cognitive ability to perform in a subsequent task is reduced. That’s why checking email every 10 minutes is an objectively poor use of your time. Feeling busy is not the same thing as being productive. And it’s far from harmless. When taken to the extreme, the result of task switching in parralysis. Computer science has a term that describes this: Thrashing.

Thrashing takes place when a computer’s virtual memory resources are overused, leading to an oscillation between trying to load and failing to load a task. This causes the performance of the computer to degrade and then collapse. In essence, the computer is not allocating enough time to resolve any one task, opting instead to task switch faster than it can resolve tasks, generating a backlog of errors it cannot clear. The computer is stuck in an infinite loop. It may even heat up and, on a Mac, display the dreaded swirling-beach-ball-of-death instead of a regular cursor.

Thrashing happens in people too. If you’ve ever felt completely overwhelmed by the number of things you have to do, be they large or small, you were thrashing. If you’ve ever felt like the anxiety created by the number of things on your to-do list impedes you from completing your to-do list, you were thrashing. If a friend has ever invited you to hang out, but hanging out with that friend (whom you love!) would create more stress for you than it would create joy, you were thrashing.

Thrashing is happening more and more these days. There is so much to balance, and for those of us working from home, the temptation to task switch is greater than ever. For one thing, our families may depend on it. For another, it just seems, well, so harmless. It’s easier to hop on a Zoom call than drive across town for an appointment. However, as far as our attention is concerned, the burden is the same.

Nevertheless, there are ways out of thrashing. The first thing to do is to recognize you’re thrashing. After that, there’s Chekhov’s Gun.

II. Chekhov's Gun

For computers, a thrashing scenario will continue unabated until the user manually resolves enough tasks (e.g., by force-quitting applications) to free up sufficient memory to enable the computer to begin resolving outstanding tasks.

A similar approach is needed for people, and luckily, there’s a nice analog in Russian Literature: Chekhov’s Gun.

Anton Chekhov was a Russian playwright and short-story writer who is considered among the literary giants. His “gun” principle states that in a story a writer should only include details that will later on become relevant to that story. If the detail is not relevant, remove it. His famous example goes as follows:

“If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.” -Anton Chekhov

Chekhov’s Gun applies to thrashing in three important ways.

1) Evaluate relevancy. Ask yourself what really matters (e.g., does checking Instagram really matter? If not, note that).

2) Prioritize ruthlessly. Eliminate the things that don’t matter (e.g., checking Instagram doesn’t really matter so delete the app).

3) Narrativize your life. Step back and think of your time on earth as a story — your life story — and what things actually make it into that tale. Doing this can help you align your choices with your long-term goals. It can also help you right-size decisions so that you don’t sweat the details or invest too little in the big things (e.g., no amount of Instagram-checking would make the story of your life materially better, so move on. Spend more time with your loved ones).

Chekhov’s Gun is more than literary technique. It’s more than a method to become un-busied. Really, it’s a convient short-hand for living a more fulfilling life.